|

For those interested in Semitic studies: SEMBASE: a database project for the study of Semitic roots

Gold Plates Touchstone Home

Gold Plates Touchstone

studies by

A. Chris Eccel, Ph.D.

|

The Weighty Issue of a Gold Bible

By A. Chris Eccel, Ph.D.

Since many involved believed that they could heft the plates, it is clear that no one really had any idea how heavy gold is. The table below reviews the options, with different metals. The accounts of hefting the plates need to be evaluated in the light of the weighty facts: if they were gold, they would weigh 135 pounds, calculated with a very generous estimate that the air between the plates could account for one third of the volume. In fact, 10% is more likely. On the other hand, the plates may have been only 80% gold, and 20% copper, an alloy called tumbaga actually used in South America in Book of Mormon times. Tumbaga plates with these proportions would weigh 120 pounds, again with the same generous allowance for air between them. It seems clear that very few witnesses would be able to heft 120 pounds. The testimonies would read more in the vein of attempts: "I tried to heft them, but could not lift them."

In the table below, the assumption that the volume occupied by the plates could have been 33% air seems more than generous. There are various estimates of plate thickness, from 1/8" to the thickness of common tin plate, perhaps 1/16". Taking the latter, there would have been 96 plates (6"X8"). Inscribed on both sides, they could have been somewhat less than flat, although the serious weight of the gold would have served to press the lower plates in the stack relatively flat and tight. Gold is a very soft metal.

Weight of the Plates (Various Metals Compared)

|

Weight of Each Option Adjusted for the Percent Air

Solid block is 6"x8"x6" or 288 cubic inches

|

Plate

option by

substance

of the

plates

|

Weight

gold

per

cubic

inch

|

Weight

copper

per

cubic

inch

|

Weight

brass*

per

cubic

inch

|

Weight

lead

per

cubic

inch

|

Volume:

G gold

C copper

B brass

L lead

|

Weight

per

solid

block

|

%

air

|

Total

(67%

of a

solid

block)

|

Gold

plates

|

.7

pounds

|

|

|

|

|

201.6

pounds

|

33

|

135

pounds

|

Copper

plates

|

|

.31

pounds

|

|

|

|

89.28

pounds

|

33

|

59.8

pounds

|

Brass

plates

|

|

|

|

.2876

pounds

|

|

|

84.64

pounds

|

33

|

55.5

pounds

|

Lead

plates

|

|

|

|

.41

pounds

|

|

118

pounds

|

33

|

79

pounds

|

Tumbaga

plates

|

.42

|

.124

|

|

|

G 60%

C 49%

|

156.67

pounds

|

33

|

105

pounds

|

Brass-lead

combo

|

|

|

.2876

Pounds

|

.41

pounds

|

B 49.5

L 193.5

|

B 56.97

L 38.75

|

33

|

76.9

pounds

|

1. The tumbaga is rated here as being 60% gold & 40% copper. So the weight of copper per cubic inch is.31x .4=.124, and the weight of gold is .7x.6=.42, and therefore:

[(288x.42)+(288x.124)]/.67=105 pounds of tumbaga.

2. The weights per cubic inch of gold, copper, brass and lead are multiplied by 288 to get the weight of a solid block. The weight of the plates for each is this time .67.

3. The weight of brass varies. Common brass for cold working applications is 65% copper and 35% tin (.246 pounds per cubic inch), and the weight of the two combined is given here: (.31x.65)+(.246x.35)=.2876.

4. The brass lead combo assumes that half (3 inches, i.e., the sealed plates) were hollowed out, with a margin of one inch on the side where the rings would have passed, like a three-ring notebook, and a margin of 1/2 inch at the top, bottom and right-hand sides. This yields a volume of solid lead (6-1-.5)x(8-.5-.5)x3=4.5x7x3= 94.5, so that the weight is 94.5x.41=38.745 pounds of lead in the combo. The brass volume of the margins of the bottom (sealed) three inches is 16.5 (area of the margins) times 3 (height of this portion of the plates), equaling 49.5 cubic inches of brass in the bottom section. The top uncut plates have a volume of 6x8x3=144 cubic inches. The total volume of the brass is therefore 49.5+144=193.5. The block weight is 193.5x.2876=55.65 and two thirds of this is 37.286 pounds. The brass portion (37.286) plus the lead portion (38.745) equals 76 pounds. Wider margins and a shorter sealed portion would reduce this.

|

|

In the case of tumbaga, although the ratio was as high as 80% gold, more usually it was only 75%, but could be even lower. It has higher tensile strength and a lower melting point than either metal alone, and can be gilded by applying a mild vegetable acid. This dissolves away the surface copper, leaving a pure gold surface film, and the process can be repeated when wear occurs. However, tumbaga does corrode:

|

|

Non-gilded archaeological metals having a high percentage of copper are known to survive in better condition than gilded tumbaga objects primarily due to galvanic forces and preferential corrosion between gilded layers and the underlying alloy in a burial environment. The less noble copper will eventually corrode, the resulting corrosion products will undermine the gilding, and the thin gilded layer may eventually become detached from the heavily mineralized base alloy.

Scott Fulton and Sylvia Keochakian (see "References" below)

|

|

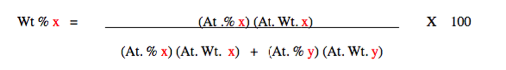

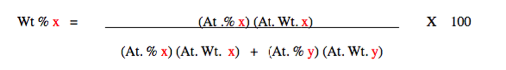

Alloys must be above fifty atomic percent (At.%) gold to be corrosion resistant. [Scott Fulton and Sylvia Keochakian (see "References" below)[ Atomic percentage is the percent of the atoms in the alloy that are a particular metal. To the extent that the copper atoms outnumber the gold atoms, they will be more susceptible to oxidation, producing serious deterioration. The following formula calculates the weight percentage when the atomic weights and atomic percentages of two metals in an alloy are known. I am using x for gold and y for copper. This example has 50 At.% (.5) for each metal.

= (.5X196.966)/[(.5X196.966)+(.5X63.546)]X100 = 75.6%

Therefore, more than 76% gold, by scale weight, is needed for the plates to be relatively corrosion resistant. If the gold is 67% by scale weight, the atomic weight percent falls to 40%. Over a period of 1500 years, serious corrosion would occur. Presumably, corroded plates with the gilding scaling off, are no one's image of Smith's gold plates.

So bearing in mind that gold plates would weigh at least 135 pounds, and even tumbaga plates would weigh from 116 to 120 pounds to survive relatively free of corrosion, we read his mother's account of how he got them out of their hiding place in a log in the woods and home:

"Joseph...wrapping them in his linen frock, placed them under his arm and started for home...travelling some distance after he left the road, he came to a large windfall, and as he was jumping over a log, a man sprang up from behind it, and gave him a heavy blow with a gun. Joseph turned around and knocked him down, then ran at the top of his speed. About half a mile further he was attacked again in the same manner as before; he knocked the man down in like manner as the former and ran on again; and before he reached home he was assaulted the third time. In striking the last one he dislocated his thumb...he threw himself down in the corner of the fence in order to recover his breath."

Lucy Smith (see "References" below)

|

|

Joseph runs more than a mile with a weight of at least 116 pounds. He carries it under his arm, like a schoolbook. With it, he jumps over a log. And during this whole time, carrying it from place to place, there is no mention that he can hardly even lift it. Moreover, he was still suffering the effects of the removal of a large abscess in a leg. Smith's mother also reportedly said that she had herself handled and hefted the plates. (Sally Parker, see references below)

Martin Harris had spent his life working on his farm, and was no stranger to hefting heavy objects. Reportedly he claimed to have hefted the plates, and said that they weighed forty or fifty pounds. (Joel Tiffany, see "References" belos) William Smith recounted that when Smith first got the plates home, although he did not see them uncovered "I handled them and hefted them while wrapped in a tow frock;" and that "Father and my brother Samuel saw them as I did while in the frock. So did Hyrum and others of the family." (William B. Smith, see "References" below) Lucy Smith wrote that she invited Mrs. Harris over to see them. In an interview to Edward Stevenson, Martin Harris stated that his wife and daughter had hefted the plates and felt them under cover; he said, "My daughter said, they were about as much as she could lift. They were now in the glass-box [a wood box for window panes], and my wife said they were very heavy. They both lifted them." (Joel Tiffany)

In summary, whether we consider the many who hefted the book, even Mother Smith, Martin Harris' estimate of their weight, or the adventures of Joseph running through the woods, the bottom line is that the sheer weight of even tumbaga plates cannot be reconciled with the story. And the weight of even these hypothetical tumbaga plates was generously underestimated.

The writing area is also a problem. The following data reveal the extent of the issue:

|

|

height of the stack of gold plates

|

6"

|

|

thickness of the platers (at the low end of estimates) |

1/16"

|

|

number of plates (16 per inch = 6X16) |

96

|

|

number of unsealed plates (using the high-end estimate, i.e. 50%)

|

48

|

|

|

|

number of engraving spaces with the plates engraved on both sides

|

96

|

|

number of BoM printed pages in the customary LDS edition

|

520

|

|

Skousen's estimate of ms O pages for Nephi thru Words of Mormon

|

124

|

|

number of BoM printed pages to cover Nephi thru Words of Mormon

|

133

|

|

estimated printed pages to cover the 116 pages of the lost Book of Lehi |

100

|

|

number of printed pages for the BoM with the lost book of Lehi |

620

|

|

number of English printed pages per gold-plate writing space |

6.46

|

|

The number of plates would be less if they did not lie perfectly flat. There must have been a margin, and a wider gutter to accommodate the binding rings. Using figures at the end of the range of estimates most favorable to the gold-plate story, the plates would have had to have the equivalent of 6.46 pages in English per side, in largely reformed Egyptian, but partly in Old Egyptian (Lehi and its Nephi replacement text). It is hard to imagine compressing any real script to this extent.

How about Brass Plates?

To cover other possibilities, it is instructive to have knowledge of metallurgy in the early Americas, as well as in early nineteenth-century New England. Smelting gold, silver and copper began in the Andes, where alloying also emerged. Well before the Common Era, bronze and tumbaga were produced. The Moche culture was especially advanced, and South American trading ships carried on an active trade with Mesoamerica, resulting in local metallurgy among the Mayas in their classic period (c. 250-900 CE).

In colonial America, the British tried to prevent the local development of the metal industries. Still, the world's largest identified lead deposit is in Missouri's lead belt, and it was being mined as early as 1720. Frontiersmen needed it to cast balls for their muskets. Prior to 1800, brass was mostly used in the button industry. Buttons were formed from sheet brass, and these craftsmen got their brass rolled in early steel rolling mills. The center of the New England brass industry came to be in Waterbury, Connecticut, the self-dubbed "Brass Town." Aaron Benedict began rolling sheet brass in 1824, and quickly found a market for his product. Joseph Smith came from a cooper family. His grandfather and father had been coopers, he was a cooper's son, and his family had a cooper shop. It is interesting to observe that this shop was one of the first places where he claimed he was hiding the plates.

The weight of brass plates would be at least 55.5 pounds, more than the upper end of Martin Harris' estimate for the weight of the gold plates. The unsealed portion of brass plates could have been easily inscribed with Smith's character set using an awl, or even an ice pick. But does this mean that the Smiths had actually produced this sort of prop for their project? Not necessarily. Everyone who claimed to have hefted or otherwise examined the plates may have been a confederate. But having a brass-plate prop would have been effective, even just for feeling it through a cloth and hefting it. After all, we do not know that all those who had this privilege got their experience into print.

Conclusions

1. The weight of the plates, if gold, is completely incompatible with the stories told about their being carried and hefted.

2. Corrosion-resistant tumbaga plates could look like gold, but are still too heavy.

3. It was possible in the mid 1820's for a cooper's son to fabricate a brass-plate prop, although there is no need to assume that this happened.

4. The writing area of the plates as described could not have held the entire Book of Mormon text.

References

Fulton, Scott, and Sylvia Keochakian, "The conservation of tumbaga metals from Panama at the Peabody Museum, Harvard University," Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Twelve (2005), 76-90.

Harris, Martin, as quoted in Joel Tiffany, "Mormonism--No. II," Tiffany Monthly (August 1859, in Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, II:306.

Harris, Martin, as quoted by Joel Tiffany in "Mormonism--No. II," Tiffany Monthly (August 1859, in Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, II:309.

Parker, Sally, to John Kepmpton, 26 August 1838, in Vogel, Early Mormon Documents (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), I:218-19.

Selwyn, Lyndsie,, "Corrosion Chemistry of Gilded Silver and Copper," in Terry Drayman-Weisser, Gilded Metals, History, Technology & Conservation (London: Archetype Publications, 2000), 21-47.

Smith, Lucy, in Anderson, Lucy's Book, 385-86.

Smith, William B., "Wm. B. Smith's last Statement," Zion's Ensign 5: Jan. 13, 1894, in Marquardt, Rise of Mormonism, 72.

Copyright: Arthur Chris Eccel

While reserving my copyright to this study, it may be downloaded for free, and cited at will, as long as it is properly referenced.

DOWNLOAD

|

| |